When we look at his recent exhibitions, we can easily deduce that during these last years, Lee Bae has given prominence to sculpture and installation. Indeed, the artist has consecrated several rooms to these disciplines in his exhibition at the Daegu Museum of Art in autumn 2014. This was also the case at the Fondation Fernet Branca in Saint Louis, the spring of that same year. The same went for autumn 2015, at the Guimet museum in Paris where he has invested the entire cupola, as well as in spring 2016 with two installations especially conceived, one for the chapel of the Domaine de Kerguéhennec, the other for the riding arena of the stables in the Castle of Chaumont-sur-Loire. But what might spark an astonishment here is in fact only a fair return of things, or, even more simply, an inscription in an obvious continuity and a logical evolution.

Indeed, the area of Lee Bae’s work we are familiar with since the beginning of the 2000s is mainly the big paintings in black and cream/white made with acrylic medium. But we have somehow forgotten his earlier works, those of the 1990s, which, at a time when he was less well known than today, were rarely, sometimes never exhibited. But Lee Bae did not lose sight of them, just as he has never forsaken the material of his beginnings: he has simply transformed the charcoal which composed them into a black ink made of coal. Surely we must not forget that besides their remarkable power, these works, which we could assemble under the heading “charcoal period,” correspond to an essential moment in the artist’s career. They coincide with his arrival in Paris and mark a turning point in his method, with the discovery and use of what was a new material for him: wood charcoal.

As Lee Bae has often repeated, there were several factors that led him to the use of wood charcoal after his arrival in France in 1990. First of all was the fact that it reminded him of his origins, the world of India ink, calligraphy, and a deep grounding in the Korean tradition with its symbolic power and poetic weight. Charcoal allowed him to combine and bring together two subjects: matter and black. In other words, on the one hand, the material in itself, and on the other, the material in the service of black.

Charcoal turned out to be a powerful source of energy in the literal and figurative senses: a concentrate of life. Lee Bae would assert the presence of this raw material, play on its physicality, awaken its existential dimension, draw out all the aspects, using pieces of different kinds to make sculptures, installations and paintings.

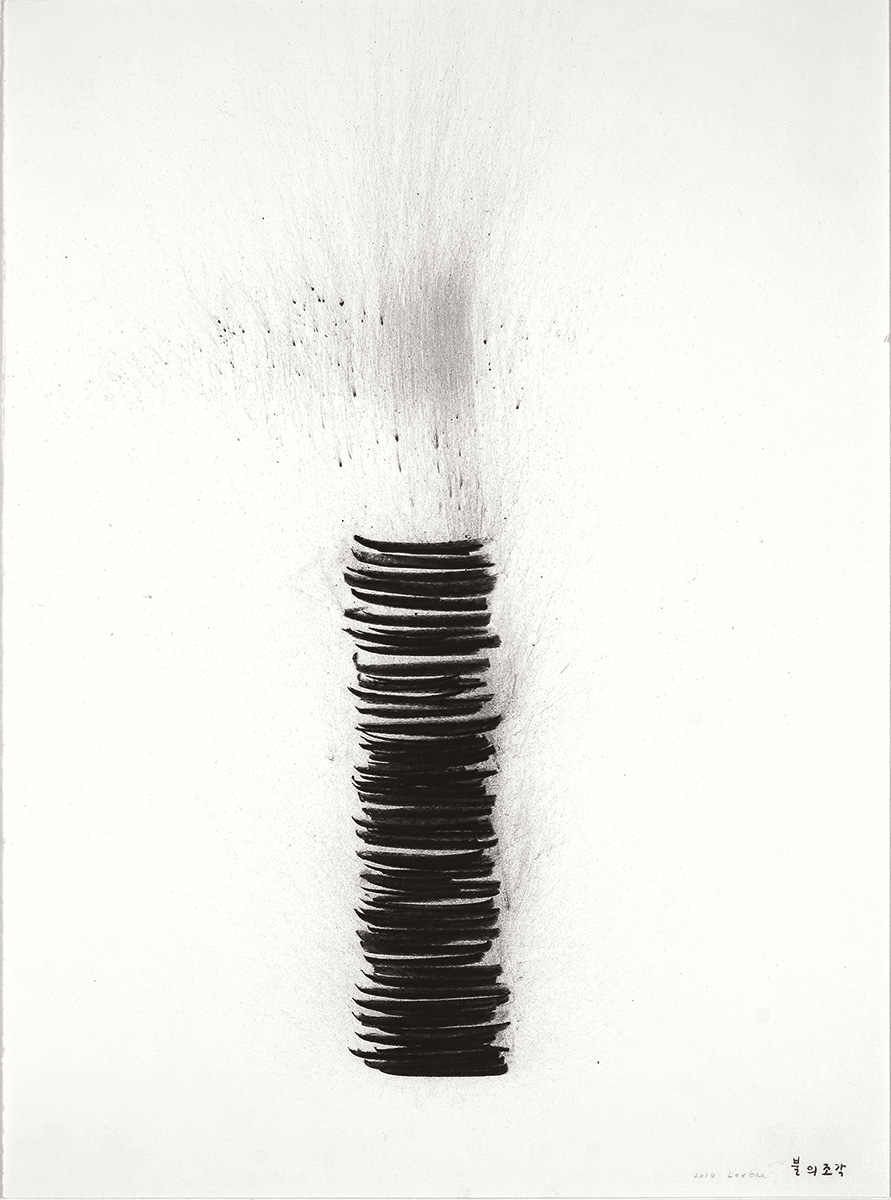

For the first, the artist fashioned the charcoal so as to give the blackness volume and density. For the installations he laid out the blocks on the floor or on the walls, as if he was exploding the material in order to make a shattering of black, to scatter and constellate black. For the pictures, the artist sharpens, juxtaposes, glues and rubs his shards of charcoal. He works at the surface, reveals black highlights, plays on moiré effects, thereby creating a mosaic of shadows and gradated shades of black. It is indeed when we see these pictures (again) that we understand the subtlety of the link with the period that followed, and how Lee Bae went from work on the planarity of black to work on the depth of black.

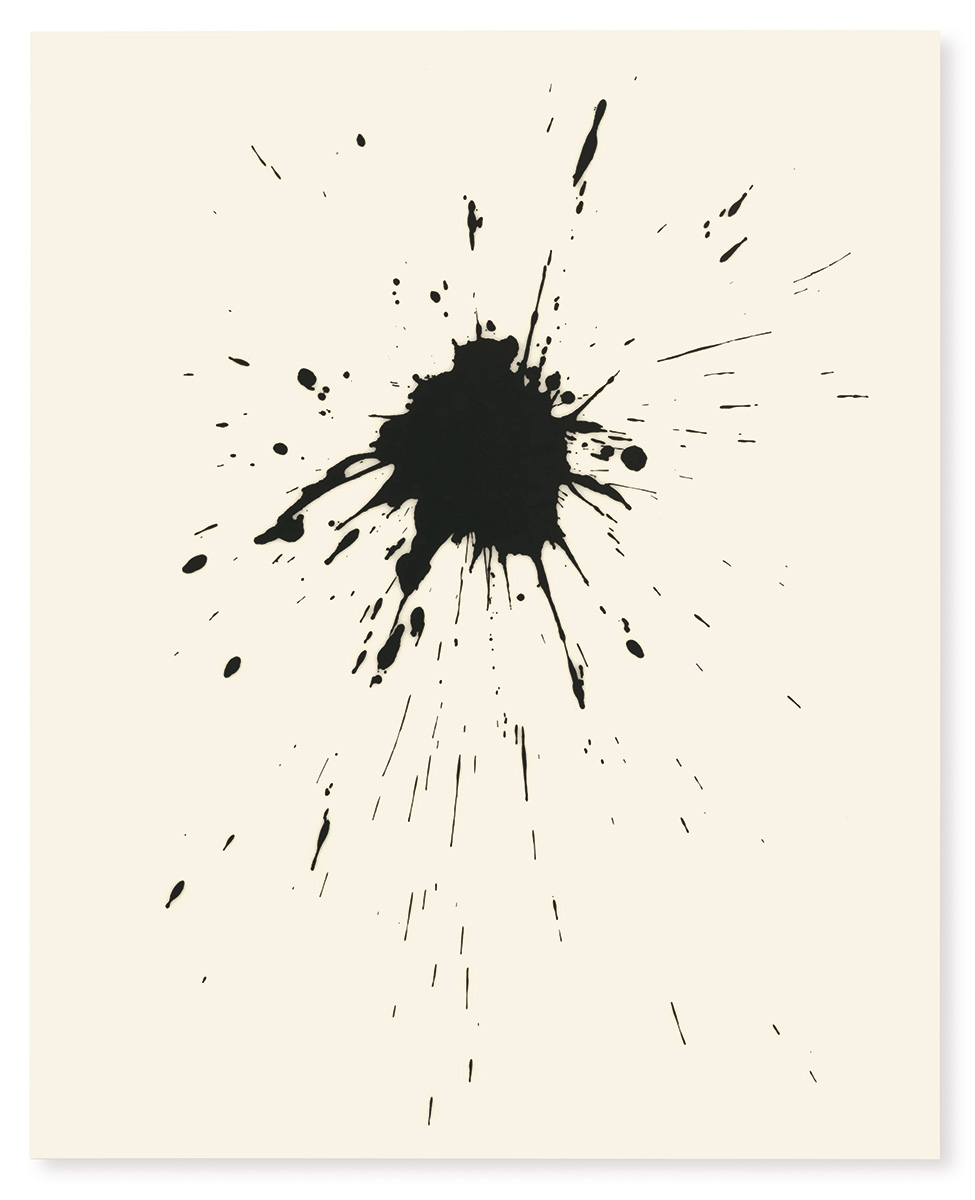

At the turn of the 2000s, Lee Bae felt the need to move away from charcoal. One day, as if making a performance or a happening, he threw up in the air the powder and the pieces he had around him – his way, perhaps, of letting the charcoal “go up in smoke.” From then on, once again with great technical mastery, he started using charcoal powder and acrylic medium, which he spreads out flat over his canvases in several successive layers.

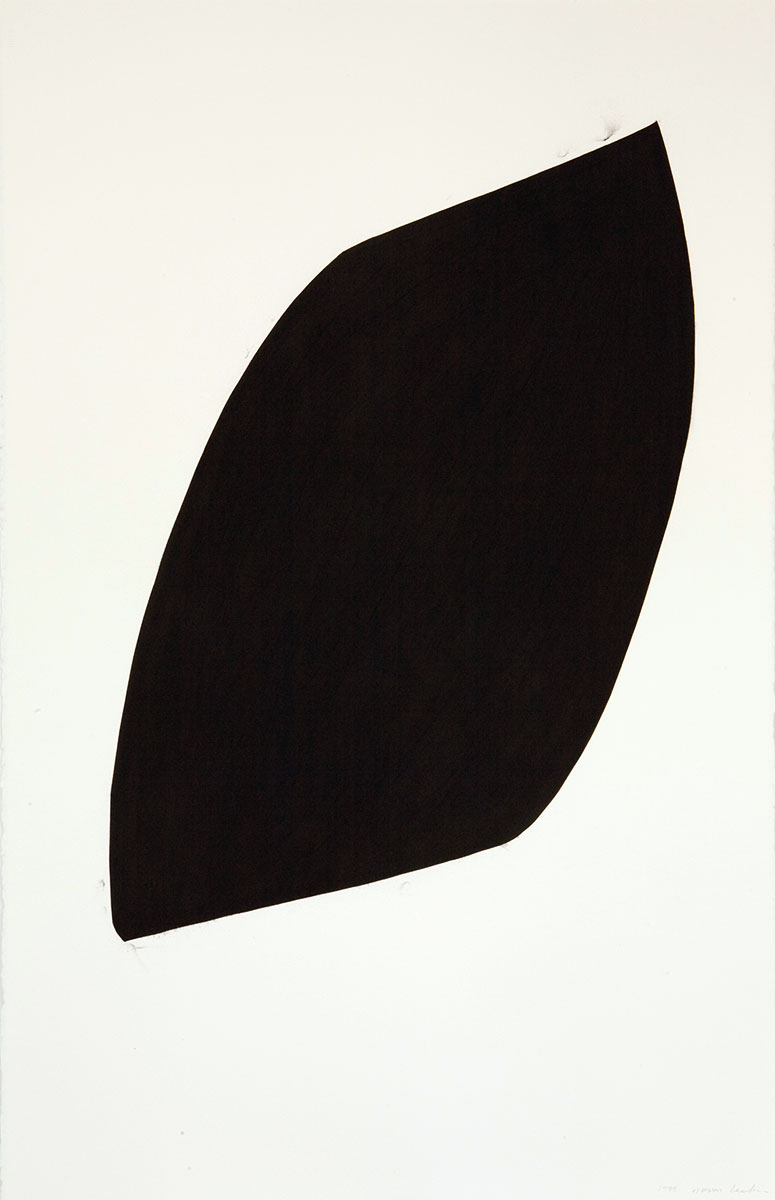

With the first material he creates a white or cream ground. With the second, a black form that seems to hang in space. In the meeting of the two the white gives even more power and intensity and vibration to the black. If the pictures in wood charcoal seemed to emphasise surface effects – although without neglecting the principle of density, which generates these effects, the canvases in black and white, in contrast, give the impression of being concentrated in the notion of depth, possible only because of the magnificent work on the surface. Attesting this is the extremely smooth, very soft, sensual appearance of the surfaces, reminiscent of wax.

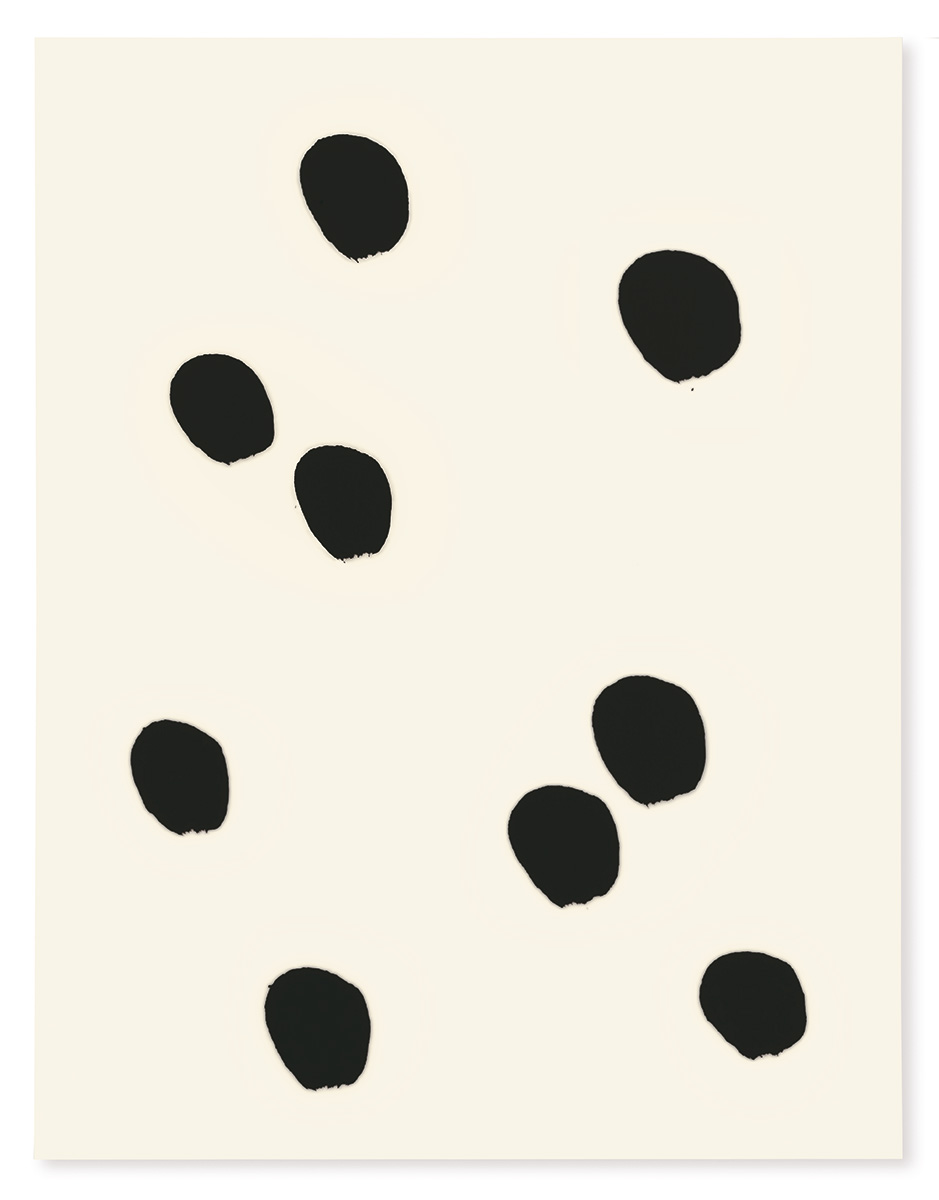

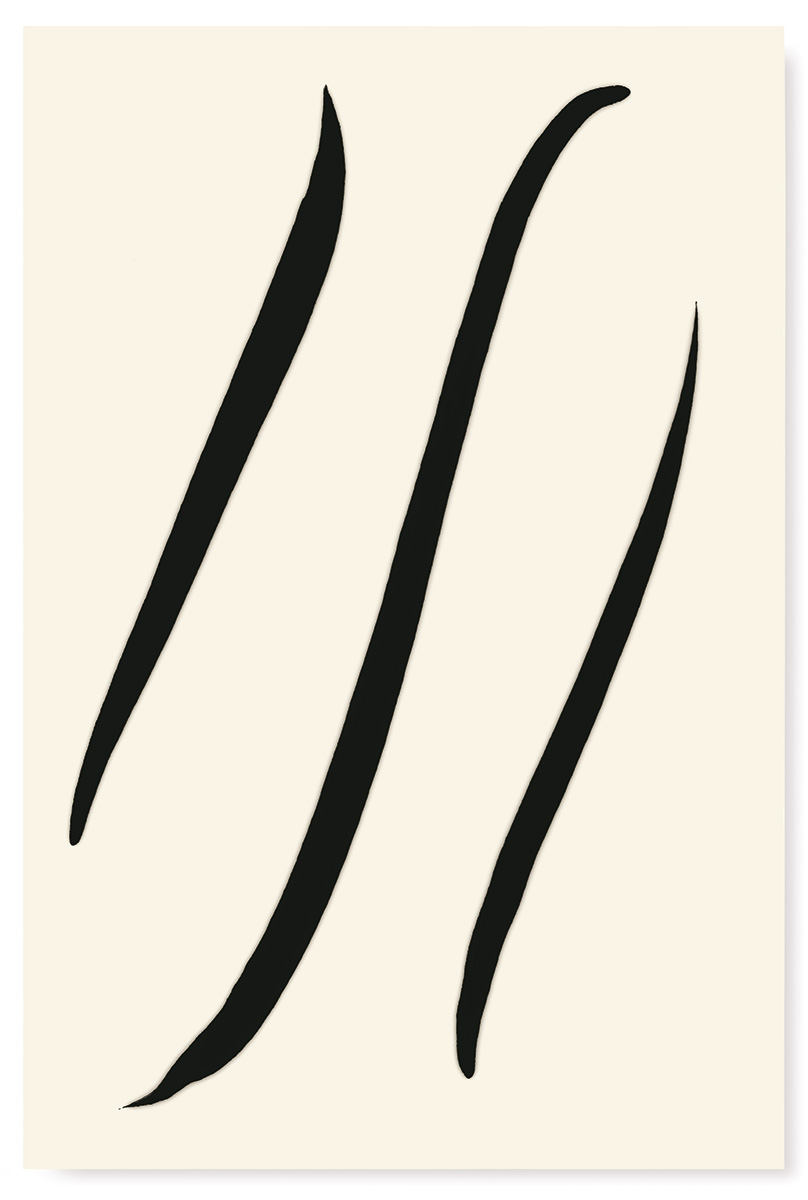

These works recall Lee Bae’s interest in material and his slow, painstaking way of working it. They bring to the fore a spiritual quest and a dimension of time that is omnipresent in his work: the time inherent in the history of charcoal and the way he works it. The time inherent in the process of elaborating his canvases, in covering them with successive layers (a way of suspending time in the space of the canvas), and in the drying time necessary between each layer, and in the great precision (extending the moment) of the outlines of these black forms. For, contrary to what we might think, there is nothing gestural or spontaneous about them. There is nothing random here. They are, on the contrary, the result of a long, experimental process of drawing. It is only after having thought about and found what he is looking for on paper that Lee Bae transposes it precisely onto his canvas. These forms, which at times evoke spirals, at others splattered marks, or again lines, curves and signs close to calligraphy, are there only to embody black, to give black a body. Neither symbolic nor figurative, they refer to nothing other than themselves, to a territory of black. We can now see more clearly why it is essential that they should be in perfect spatial harmony with the expanse of white. The equilibrium of their distribution cannot tolerate the slightest disproportion. For the dialogue between them to function, great exactitude is needed. For it is of course from the encounter, the confrontation between these two colours that these black continents emerge; from that frontier which at first view seems to quiver because of the subtle reflection of their contours in the translucency of the whiteness, that the black rises and vibrates. Then all we can see is this black body, this mass with its extreme tension, its tremendous energy, possessed of an incredible density that sucks in the light and our gaze with it. Like a bottomless black well, with its secrets and backgrounds, where each person finds the depth they want to see and the vertigo they are ready to feel. Like a black hole in the astrophysical sense of the term with its ultra-compact matter – like, here, this black that contracts into itself, this black that plunges into blackness, to infinity. A beyond-black. This, we had already seen in his earlier works made with charcoal, and we discover it again today. A charcoal that Lee Bae knows how to transform so as to turn a cultural element of his origins into a universal language.