Standing Outside

Sim Eunlog. Why did you move to France in 1989? New York was already the center of the art world among other things at that time, what made you decide upon Paris?

Lee Bae. I was thinking to work on my art outside of Korea for a long time. To leave a place that one has become familiar with is an act of desire out of fundamental human will to objectively look at one’s Self. In the beginning, I visited New York many times for a possibility to settle there. America definitely has many lively sectors, and I really felt their strengths. However, if I may say so, art felt more commercial than being art itself. There, I felt as if the artist were simply lingering on the market grounds. New York was undoubtedly the most important place for art and other sectors, but I was afraid of settling in an market-like place. So I agonized over where was a suitable place I could go to construct my art and mature myself as an artist. I felt this was possible in Paris, and so I moved there. Time passed, and so I stayed. Looking back, I really feel that Paris was good for my artistic development.

Shim Eunlog. In Korea, you created colorful abstractions using paints. Once you moved to Paris, you began monotone works from charcoal. What caused this change?

Lee Bae. When I made drawings in Paris, I used a slender stick of charcoal, but I was not fully satisfied with it, so I bought a whole bag of charcoal for grill. As I drew with charcoal, I was fascinated by its texture, and also brought me back to the very first time I began painting. An artwork I made very early on was made of mashed up charcoal made to look like a drawing. Even if charcoal is common and shabby matière, it can deepen in its meaning if it matches well with the artist and connects with his artistic sensibilities. If the artist can find a material he resonates with, and spends a long time with it, that material can stand out as a projection of the artist’s image. There was also a financial reason for using charcoal. Paints were particularly expensive, and charcoal was comparatively very cheap – and I could use one bag of charcoal for a really long time.

Sim Eunlog. Because the matière in France was so expensive, you searched and developed use for a new matière, and in the process, your art found new form. Your path seems to have been opened via adversity.

Lee Bae. And so time passed since my encounter with charcoal for simple reasons like that, and I began to think of the concept of the great Asian Civilization, something that always naturally enters the artistic background for anyone who is Asian, with the color black. Could I say my cultural scent leaked out? In Eastern painting, black is a color that encompasses all colors – subtle pink cherry blossoms, white orchids, yellow chrysanthemums, green bamboos – all can be expressed with black.

Sim Eunlog. Actually, charcoal can be seen on the cave walls of Altamira, Lascaux and Chauvet; surely an indication of the most original artistic matierre as expressed by humanity. From a purely optical point of view, black can only be created through the absorption of all other colors, so your saying that Eastern ink encompasses all colors really makes a lot of evidential sense. In fact, other colors cannot express that same nuance. Charcoal or ink drawings seem to hold humanity’s age-old aesthetic memory.

Lee Bae. Sure. I actually dig out age-old memories from my inner self through a point of contact with the external. For example, when I look at the food at my mom’s house, I have only flickering memories of the fact that I grew up eating this. However, at the moment that I taste the food, that old and familiar taste brings out a flood of related sensations and sensibilities. My conscious self could not quite remember it, but my body could. Like the finding of previously lost taste by the tongue’s aesthetic, experiences and sensations through the physical body can pull out the fragments of what has been completely forgotten – by the body’s contact with external stimulation. Similarly, my body unconsciously paints and at the end, results are a kind of memory fragments that comes from my body. My art is the continuous refinement of such a process.

Sim Eunlog. As you said, the body holds a great number of “memory fragments”, but most people lose them at a flash of the moment, like evaporating flavour. These memories end with a short exclamation – “Ah!” Today, there is little interest in what hides behind this, “Ah!” It is considered a pain, I suppose. However, Marcel Proust has written seven volumes about the involuntary memory of the madeleine scent drenched in his tea.

Lee Bae. So different from European literary figures or artists, if I may say so honestly, I was not raised in an culturally stimulating environment for painting; I was a country boy who grew up in the countryside, like a tough weed. As someone from such a poor place, overwhelming the richness of western culture, I realized that my art began from a lack of imagination, and I tried to absorb any kind of inspiration around me and it became ironically in fact the source of my art. Instead of squeezing out my lackluster imagination, I became more interested in connecting together the vast imaginative world that was strewn out there outside me. The issue was simply how to connect them. I used the expression, “imagination”, but this can be rephrased as, “the environment that creates images” and can be regarded as “artistic motifs” by other people.

Sim Eunlog. So how did you connect all the pieces of imagination that are floating about out in the world?

Lee Bae. Through memories. This memory becomes the instrument or tool that connects these external or outside imaginations through what I mentioned as “sensations”. Memory has the temporal meaning of what has passed, but my meaning also encompasses environmental and spatial elements.

Sim Eunlog. Other than using charcoal, you also made delicate drawings out of staples. How did you come to use staples as matière?

Lee Bae. For the first 6-7 years in Paris, I was an assistant to Lee Ufan and helped him to spread canvas sheets on frames using staplers. One day, the stapler felt to me like a pencil. At that time I was totally absorbed using charcoal, a matière of nature. But if charcoal is of nature, the stapler was of the industrial society. I wondered whether I could make use of a product of our industrial era, the stapler became my choice. Likewise, an artist’s work is usually very related to the condition of his own life and environment.

Charcoal, A Fragmented Memory

Sim Eunlog. After your solo exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea in 2000, your art went through considerable changes. Why did you stop using charcoal?

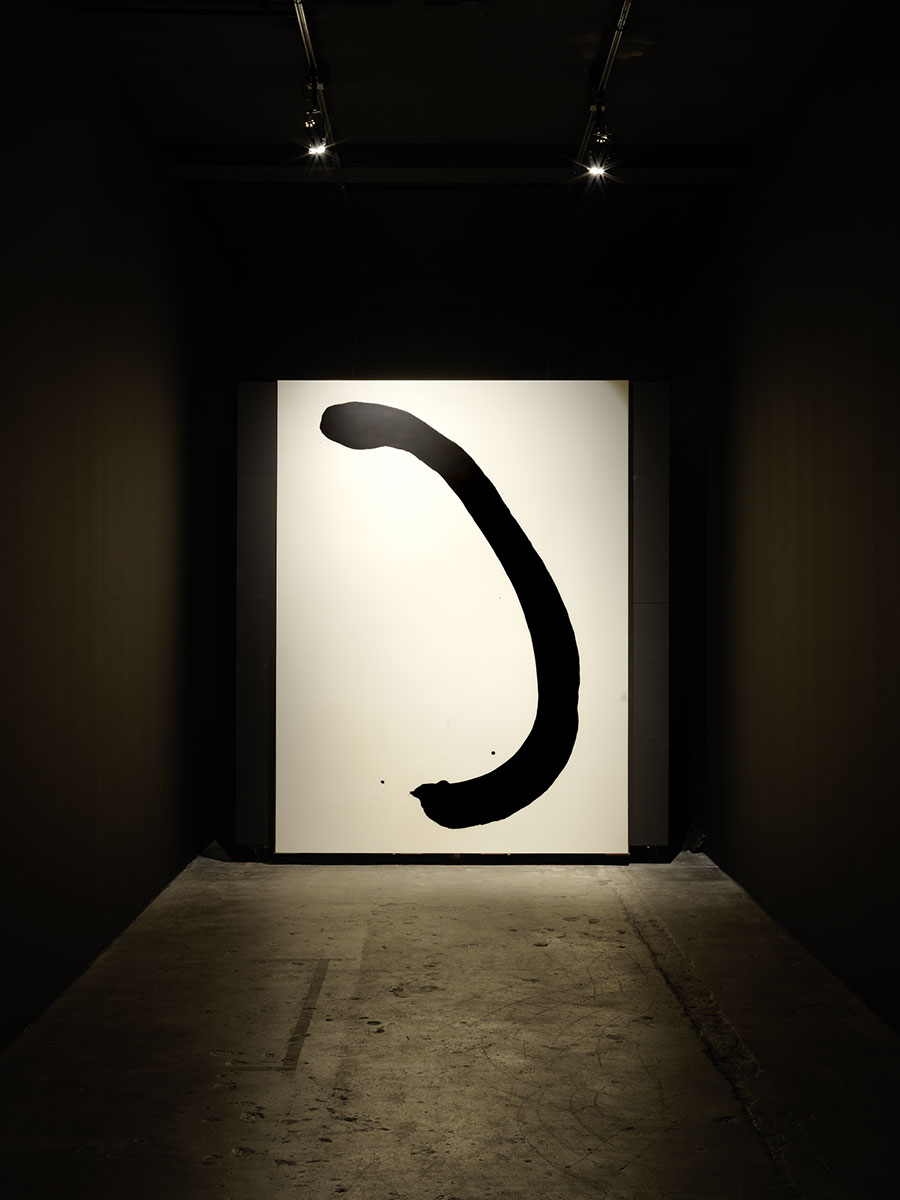

Lee Bae. I didn’t stop using charcoal. The way I used charcoal has changed. I began to be known through ‘The Artist of The Year’ show at the NMMCA in 2000. Afterwards, however, I felt I was overly-dependent on the materiality of charcoal, and began to worry about how to get it over. As I thought about showing less of the materiality, I thought of what to do with acrylric medium. This acrylic medium had very ambiguous sense of materiality. I used it to give ambiguity and depth on canvas. On it, the black strokes of charcoal powder medium mixture are drawn, I said strokes but what is important to me in this work is the gesture that I made with this material. In this way I’d liked charcoal to transcend its materiality, like smoke floating up into the air. It is the “transcendental memory of charcoal”. It left the traditional idea of charcoal, but it will always still be charcoal.

Sim Eunlog. If that medium was the supportive material to your charcoal paint previously, the medium has now gained recognition of its independent existence from charcoal. In your recent works, I don’t feel that ambiguous physicality of medium, but an ambiguity in your use of charcoal. Something about the placement of the motif on the canvas also causes ambivalence. It feels like it is sinking, and floating at the same time.

Lee Bae. My previous works had charcoal protruding out of the surface. My recent works on the other hand, withdraws the phenomenon of painting inside the surface, and the matière does not look at all as if it is sitting on top of the external surface. In Western oil painting, the paint material causes it to accumulate on top of the canvas. In Eastern painting, because of the property of rice paper and ink, the ink gets absorbed into the rice paper. In other words, Western painting piles things up on top of the canvas, whereas Eastern painting lets things become absorbed into the surface. I made use of this idea in a recent work to compromise the two different conceptual ways. With acrylic medium, I tried to make an impact that the pigment was coming up from the bottom of the canvas, but at the same time that it was falling into the canvas from the top. The rice paper looks simply a sheet of paper in 2 dimension but as soon as the ink gets absorbed, you can see the myriad of layers the rice paper is made up of. It becomes 3 dimensional and I wondered a lot how this could be recreated.

Sim Eunlog. I have often seen many Asian artists working on Western painting trying to neutralize their Asian scent, although this can be a great impetus. In your case however, you actively adopted the Asian mindset.

Lee Bae. I’m not trying to differentiate what is Eastern and what is Western. My art is about how our physical, human bodies are platforms for the exchange of age-old memories and the external world. Our bodies are medium of the external world and it has a lot of memories related to the external world. This externality differs from one’s own memories. When we actively embrace these environments and try to represent it in Art, I believe a great inspiration and strength comes out of the work. Interestingly, in the case this inspiring force is elevated, the art crosses spatio-temporal borders to become synaesthetic, regardless the specific environment.

Sim Eunlog. Neither was I trying to differentiate Eastern from Western art. By comparing them, we could recognize their differences, and with this upon the background, I wished to deepen and develop our conversation. So first, what do you think are the fundamental differences between Eastern and Western art?

Lee Bae. In Asia, especially the literary painting, there is emphasis on creating metaphors for a state of mind. Fundamentally, rather than trying eagerly to do art itself, Eastern art is trying to reveal the metaphors for reaching a certain mentality or an elevated consciousness through art itself. On the other hand, Western art tries to make art itself, and in great earnest. Because of such differences in mindset and technique, it is not easy for a Westerner to approach Eastern art. Westerners will only draw near if you take something small and simple, but something that will interest them, to create a sense of curiosity. But if they think, “Oh that? I already know all about that,” then they will lose interest.

Sim Eunlog. Oh! You are very frank. As Lee Ufan often says, “The truth likes to stay hidden.” It is the cunning nature of knowledge.

Lee Bae. That’s right. It is why in art you will fail if you directly input the answer on the surface. You have to provoke curiosity – “What could this be?” The viewer will then prick their ears to the surface to hear what the artist has to say.

Sim Eunlog. In your video, what kind of ceremony is, “moon-house burning”?

Lee Bae. There is a ritual called “moon-house burning” at the first full moon night of the year in lunar calender. To my knowledge, there are various versions in different regions, but what you saw in the video is what we do in my hometown at Cheongdo. You make a moon-house out of pine needles and straws, like a Native American tent, people write down their wishes on scraps of paper and tie up to the moon-house. When the moon rises, the moon-house is burned, and people pray for wishes to come true, and for good health and safety for the next season.

Sim Eunlog. To release your wishes to the sky through smoke, and to pray for them to come true – it reminds me of the ancestral rites of Ancient Greece or Ancient Rome – or even offerings as told in the Old Testament.

Lee Bae. In the ancient times, the one way to pass on your message to the skies was through smoke. The using of smoke must have truly come from humanity’s common sensibility. They tried to communicate with nature or spiritual beings in that way. I’m suddenly reminded of a childhood memory. One winter, I was playing with fire with a friend of mine, and burned down a shed that was next to the creek. Of course, we weren’t burning a moon-house down.

Sim Eunlog. Oh dear, that could have been serious. You burned the whole thing down?

Lee Bae. I have no idea. We just ran away as soon as it caught fire. I don’t actually know what happened. But we were tied up for a while to persimmon trees as punishment. (Laughs)

Sim Eunlog. Why persimmon trees? I now recall you have a drawing series that had persimmons in them. They each carried very distinctly unusual expressions, and I was impressed by their expressive variety.

Lee Bae. There wasn’t any particular meaning to persimmon trees, rather my village simply had a lot of persimmon trees so I grew up with them. Some persimmons were firm, some slightly dry, some had very strange shapes, some you couldn’t tell if they were persimmons, some like raisin in the sun that they would break apart at the very slightest breeze – and I drew them all. For the exhibition however, I didn’t have such temporal or formal order to the arrangement of my artworks.

Sim Eunlog. I never grew up with persimmon trees, so I never knew persimmons could become misshapen like that until I spotted an intact one in your artwork. When I realized they were persimmons, I found myself looking for a reason that made them so changed, in what order the paintings were arranged and a certain transformational order – from the first sound one to the most altered – as if they were part of a puzzle. With a temporal or formal order, I do not know if I would have had felt that same excitement.

Lee Bae. My village also had pine trees. The turpentine for oil painting that’s made from distilling the pine resin is redolent with the scent of pine needles. One day I wondered why I liked oil painting so much, I remembered eating pine needles when I was young. I re-found charcoal, persimmons and pine needles because I left my hometown to another country. There was the fact that I missed my home, but it was more so that I had given myself a certain distance. As I looked from the outside, the inside began to show.

Repetition and Interpretation

Sim Eunlog. Your paintings have a calligraphic nature perhaps, and I am reminded of Lacan’s words: “Symbols are eternally floating off the signified.” You create art that is grounded upon material, not on non-material words, but I see that both have the important task to express or represent.

Lee Bae. Literature, art or music are all expressive. Perhaps symbols and the signified may not concord in language, the gap between the words used to explain the artist’s resultant expression, and the artwork itself, is even greater. I sometimes listen to interviews of musicians, writers and other artists. When they explain their art, what the writers say is very much in concordance with their work. On the other hand, the musicians for example, seem to me they say something so remote from what I feel about their art. I think artists are somewhere in between. Literature is already expressed with words, but music starts from a place outside the realm of reality so there are parts that cannot be expressed with words. Perhaps for this reason, I also have the musical attitude for appreciating music without trying to figure out the composer’s intention or the need for much interpretation. However, in contemporary art, people try to interpret with words instead of trying to feel. I believe feelings or emotions are important in art as it is in music. The artist exchanges his feelings with the viewer with what happens to be that one motif. To say that you saw a persimmon in my art, that you saw insects, or to say there are quadrangular and triangular motifs in my art has no meaning. That’s to talk about the concept without its body or sensibility. You need to feel.

Sim Eunlog. That is quite right. It would be meaningless to say, “I saw chairs” when you’ve seen Joseph Kosuth’s “three chairs” or Joseph Beuys’ “chair” or even Van Gogh’s or Gauguin’s “chair”.

Lee Bae. Actually, even if the artist isn’t lucidly aware of his feelings, he expresses them through the hand that is connected to the heart. To say that a picture has a triangular structure, and the apple was drawn in the style of Pointillism, is to put the interpretation first. It is the same as saying that the second stanza has been repeated five times when you listen to music. You must first try to feel, and see the picture with repetitive feeling to deepen the feeling, and it still won’t be late for you to interpret.

Sim Eunlog. I suppose that until now, the artist is constantly confronted with what is present now and what is eternal in relation to his or her art. Contemporary art these days however seems to have certain sensitivity to what is present. Perhaps the present has an intimate relationship with society.

Lee Bae. Literature, art, architecture, and all things that are art are directly and indirectly connected to something societal. Music however, has much weaker connection. I have been thinking for a long time why music has such weak connections to society compared to other arts, if it is an art form that directly deals with human sensibilities.

Sim Eunlog. Perhaps it is because our peripheral senses always want new stimulations, but the elevated sensibilities that tug at our heartstrings don’t change?

Lee Bae. Contemporary art is an artistic response to the contemporary society through the incorporation of mechanics, videos, music, sociopolitical events, philosophical ideas and so on. However, music does not have the matière to connect itself to social phenomenon or human society. It contains absolution, transcendence and the sublime, which is why the audience’s souls reverberate to music regardless of its school or epoch. In this way, perhaps there isn’t much reason to be tied to temporary social phenomenon or humanistic conditions.

Sim Eunlog. Even if music is not direct or concrete like literature or art that is sensitive to social phenomenon and the conditions of humanity, I am fascinated to hear you say that music appeals directly to human sensibilities. The composers’ effort to stay relevant to a grounded reality seems to continue.

Lee Bae. John Cage (1912-1992) was an revolutionary figure in any genre of art in 20th century, and I think of him as very courageous in accepting the external world. He was fascinated by the East, especially by the Japanese Zen Buddhism scholar, Daisetsu Suzuki (1870-1966. He spread Japanese Zen Buddhism to the America, and was the bridge between the East-West philosophy and religion), and incorporated it in his music. European interest in Eastern philosophy was at its peak at the time, especially from the US and Germany; I feel that it really was the beginning of the East-West conceptual approach, like engraftation. There was of course interest in the East before, but it was Eastern art from the westeners’ point of view, an extremely limited concept – of China’s Confucius, Japanese ascetism, zen – was thought to be the entirety of the Eastern consciousness. As he tried to adjust his point of view as the Other, John Cage saw the point of view of the Other as the Other, and through the eyes of Other, he tried best to see his own Self. He asked the audience for a similar paradigmatic shift of perspective.

Sim Eunlog. What about Eastern thinking do you think most influenced the West?

Lee Bae. The first is related to our differences in what we think is “absence”. Not the Western philosophical, nihilistic concept of nothing, but having a lifestyle dimensionality of emptying oneself, or the practical meaning of absence that is encompassed in the idiom, mu-wee-ja-yeon [Let nature be as it is]. Eastern “absence”, is different from its practice and application from the Western conception. If the West emphasizes on filling up the head with knowledge and culture, then the Eastern mindset places greater importance in emptying the Self. It is in this way that John Cage’s representative work, 4’33 becomes important, and more so that the idiom mu-wee-ja-yeon seems appropriate. John Cage finger pointed out the greatest soundscape around us without any kind of sound interpretation.

The second is about repetition, in that “There is nothing new under the sun”. The West sees little meaning in things that repeat, and may even regard it as futile. In the East however, we repeat what is meaningless, and realize early that you can find meanings throughout repetitive practice of meaninglessness.

Sim Eunlog. I wonder if the differences in meaning for repetition were because in the West, they had a very linear perspective of time, but in the East where agricultural farming was important, time was more circular.

Lee Bae. That’s true. However, as the East and West collided more often, we began to share many things. Gilles Deleuze then established the importance of the differences that occur in repetition through philosophy. In fact, sports players, musicians and artists repeat themselves for very small differences in the things they do.

Sim Eunlog. Sarkis said this in a recent interview: “Repetition is just another interpretation.” I think the French word, “interpreter” is a most apt word. “Interprete” is the most honorable purpose of a composer, and as he repeats the music, he interprets his own Self. In art too, repetition and interpretation has created many new forms since the ancient times, such as the Romans emulating Greek sculptures, and contemporary individual now creating “appropriation art”, for example, Richard Prince, Sherrie Levine, Cindy Sherman and Barbara Kruger. I see their artworks from the musical perspective of “interprete”. Your artworks also contain such repetition and interpretation, yet in a different way. They repeat almost the same motifs three times, but these three times accumulate differences in their repetition. The differences that accumulate in the three times they repeat becomes cloudy, the boundaries of the geometrical figures or symbolic motifs and empty spaces become ambiguous.

An Artist’s Conditions, The Fear of the Unknown

Sim Eunlog. At your exhibition, “Issue of Fire” (2000), I remember a viewer commenting, “Isn’t this Soulages’ “Outrenoir”?”, and upon closer examination, was even more surprised that the matière application was so different. Do you feel any identification with Soulages?

Lee Bae. Soulages once said in an interview, “What I am trying to do is what I do not know. What I do not know is what I am doing,” and it left quite an impression on me. He’s not doing something he knows, but something he doesn’t know. The universal human condition is that our Selves live endlessly together and mixed up with time, environment and the unknown Other – what we don’t know. Even if we aren’t aware of it, we constantly clash with the unknown, and live by accepting the unknown. French distinguishes fear of the known as “peur” and fear of the unknown as “craint”, and what we do is to accept “craint”. It is a fundamental fear to be afraid of the unknown.

Sim Eunlog. I see now that I’ve mistaken, in a sense, my fear for the external world and the Other as “peur”, when it is “craint”. What kind of fear did you feel when painting the unknown?

Lee Bae. I have never felt conviction about what it is that I’m going to draw. Different kinds of processes and methods were created in my life through age-old habits and repetitions, and I believe this is how my work is created. Through the construction of such a way of life, and also the accumulation of time, I come to feel my Self. Nevertheless, I feel self-consciousness whenever I draw, that goes, “What I am doing is something that would give me an endless sense of insecurity.” On the other hand, if I erased such uncertainty about the unknown, or, if I knew what exactly I was doing, my interest would also disappear, and I would no longer be painting. Also, fear endlessly – for small or big concerns – makes you question, “What is it?” Perhaps the procession of such a question might be, after all, my authentic pursuit.

Sim Eunlog. Is your or Soulages saying about “I know. I don’t know” related to the domain of knowledge or cognition?

Lee Bae. When Soulages says, “I don’t know what I am doing,” he is simply saying he opens up to the uncertainty of the outside world, or, to call it the realm of inspiration. I also vaguely feel that I rely on this type of inspiration. I am not talking about the inspiration that comes out of my own head, but the inspiration that comes from the outside.

Sim Eunlog. In French or Ancient Greek, what comes in from the outside is known as “inspiration” or “in-spirare”. It does not come from within you. Interestingly, what goes out from the inside is to exhale: “expiration” or “ex-spirare”. Do you not think that there are some gaps between art and the quotidian of reality?

Lee Bae. I think it is impossible for art and life to harmonize. I am not neglecting the possibility that some individual can do, but I would think most artists are like me. I do not paint by following my life, but I live by following my art. My focus is not upon reality, but upon art, and I live through reality by following art – and this focus is not in synchronization with the focus of life’s reality. When I have to choose, when I need a perspective on a relationship with reality, the decision comes from art. There are people who focus on honor, knowledge or family, but an artist’s concern is art. Art becomes the conditions of my reality, and one can say that I live life by these standards. People have a different focus in their lives, and that is why they think my life is very obscure.